What was it like? What did you see? Did you go to the … freak-offs? People have been asking me versions of these questions since the news came out.

It’s been a complicated year to be a former employee in the once-sprawling Sean Combs empire. But I can finally say it here: I’ve been to two parties at Puff’s house, and unfortunately, they were among the best parties I’ve ever been to.

But my (largely one-sided) relationship with Puff began many years before that.

***

I was just seven years old when I first heard his voice. I was listening to my then-favorite rapper’s album, Mase’s Harlem World, and a silky, confident talk-rap would seep into every track. I didn’t know whose voice this was, but the album — and the world it inhabited — made an enormous impression.

This was the Shiny Suit Era. A singular time that I happened to be coming of age in as a hip-hop fan. Puff was its architect and central figure; the hitmaker and driving force.

It’d be years until I dug into real lyricists and differentiated between popular and important hip-hop music. And so, I listened to “Bad Boy for Life” before I ever heard “Dear Mama,” “Fight the Power, or The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill. In my pre-teen mind, Puff was hip-hop, as far as I understood it.

With time, I broadened my tastes and immersed myself in the culture. But Puff was intertwined with all aspects of hip-hop fandom. He was, somehow, always present. He popped up on songs I didn’t expect to hear him on, in music videos I didn’t expect to see him in, and later, in movies that played to my music journalist sensibilities.

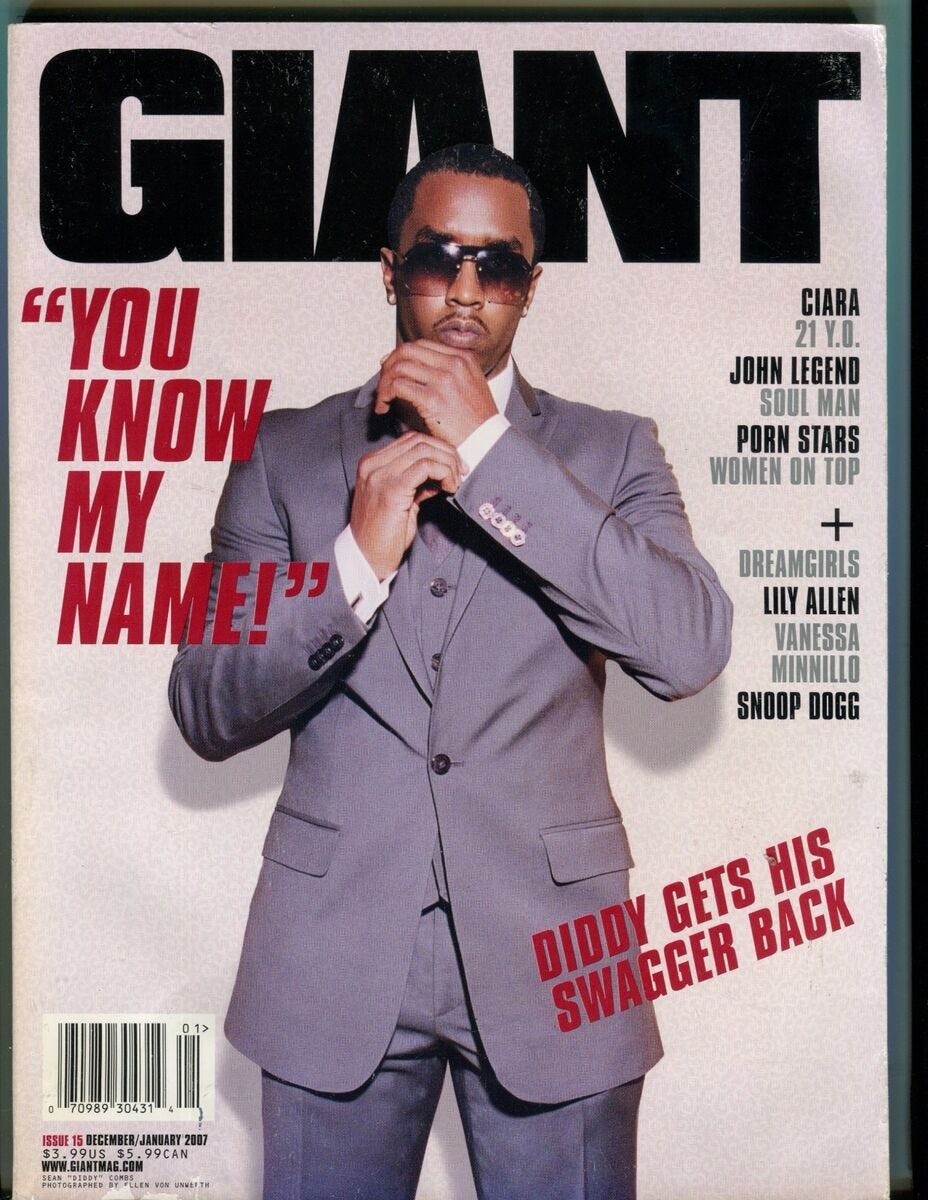

When I started my first internship at GIANT Magazine, his face adorned the cover of a recent issue. I visited my brother’s Kips Bay apartment with a copy and learned that he was a superfan. He loved Puff’s style, the way he built his businesses, and embodied every aspect of the new-age entrepreneur, stretching his empire across fashion, liquor, and corporate sponsorships, all while never slowing his partying.

Years later, as my tenure at XXL Magazine — another magazine Puff had covered many times — was coming to a close, I’d heard rumblings that Puff was launching a TV network that centered music; the millennial answer to MTV’s Teen Mom-ification.

I loved this idea, and felt there was a space for it among music fans. So I pestered my friend, a new staff writer there, for a job. I joined the ranks in August 2013, just weeks before the launch.

It was an electric time.

REVOLT had assembled some of the most talented people in the industry — writers, editors, hosts, filmmakers, creative directors, curators, producers, programmers, and talent bookers — to come together and create a television network from scratch.

Leading up to the launch, Puff was everywhere, his marketing mind going into overdrive.

He seemed to come up with a crazy concept every morning, then pull it off with the team around him. One night, he took over Times Square and held court from atop a yellow cab. Another night, he popped up at Fader Fort — a historically indie concert series — and posed for pictures with Deerhunter’s Bradford Cox. It was all happening, and we all felt like we were a part of it.

Puff’s energy was infectious, that way.

Between round-the-clock working sessions, the REVOLT staff would gather and have heated debates about new music. And when it came time to work, we would go spend time with an artist and film the exchange on a Canon 5D, and it’d be on TV later that night. It was pure magic.

But within months, reality set in.

The novel idea transitioned into a functioning business, and people fell into old patterns as it pertained to Puff. For as long as he’d been a hitmaker, producer, and impresario, he had also been a problematic boss, wielding his power through intimidation and control.

You didn’t have to look further than the cheesecake run on Making the Band, in which he demanded aspiring artists walk to Brooklyn to fetch him dessert, to understand his management style. His mindset was that if you wanted something, you had to prove it, and show how far you’d go — and how many people you’d step over — to get it.

There has been no shortage of exposés about Puff’s erratic nature. In a recent essay, former VIBE editor Danyel Smith recounted Puff threatening her life over a cover story. Earlier in his career, he was suspected of framing one of his artists for a shooting at a Manhattan nightclub, and prior to that, he was connected to the deaths of nine concert-goers at an event he promoted in Harlem.

Still, he persisted.

Puff was the ultimate manifestation of the “hustle mentality.” It’s what a lot of people, like my brother, loved about him. Even I’d be lying if I said I didn’t watch this video in times when I needed to find motivation.

He demanded greatness, of himself and others. This was par for the course in hip-hop culture, and maybe even culture writ large at the time. The Grindset. Girlboss. Win at all costs. You remember.

Back at REVOLT, Puff’s demands soon started to trickle in.

When his associates released albums, we were nudged to post favorable reviews. When artists he was courting were in the news, our coverage disproportionately focused on them. Once, on a random Tuesday, we received an email from Puff’s assistant telling us that he should, from now on, only be addressed as “Mr. C.”

Another time, when a colleague was literally on his way to a shoot that wasn’t scheduled to begin for several hours, a member of Puff’s team called him and rhetorically demanded, “Do you want to be great?”

Puff’s mere presence could be forceful and unnerving. Every time he came into the office at the corner of Broadway and 55th, there was a tangible anxiety across all five floors. People dressed better, looked busier, and hushed their voices, in the off chance that he walked by their desk.

And then there were those who wanted to get even closer.

We watched as staffers jockeyed for position and steamrolled others to curry favor. Sometimes they’d accomplish their goal, and look down on their former equals, only to be discarded and return, wondering if it was something they’d said.

Puff was hip-hop’s Logan Roy, really. If you were in his good graces, the sun shined on you and you felt invincible. But once he cast you out, you were as good as dead, or at least you felt like you were.

In reality, Puff was incredibly careful about the people he let get close. Some of that may be due to trust issues from a complicated and painful life, or his outsized status as a cultural superstar.

I have multiple friends who shadowed him for years, capturing his every moment on camera, in hopes of releasing the definitive documentary about one of the most influential figures of our time. But inevitably, the doc would get shelved, the footage discarded (or filed away in one of Puff’s homes), and the filmmakers told to move on.

I remember pitching his team a memoir, after my friend Neil Martinez-Belkin published bestsellers with Gucci Mane and Rick Ross. Puff’s fame eclipsed both of theirs, and there seemed to be so much potential in an autobiography. I was told he was already working on one with Barry Michael Cooper, but that project never came to light, either.

(Puff seemed intent on telling his story, but as soon as these deeply personal works started to materialize, they had a knack for disappearing. Perhaps he felt conflicted because he — or they — couldn’t share the full picture.)

Despite being such a public figure, Puff was enigmatic and mysterious, surrounded by layers of friends and security everywhere he went.

In 2017, I was hired to direct a Showtime promo for the McGregor-Mayweather boxing match, starring Mark Wahlberg and Diddy. I’d been out of the REVOLT whirlwind for years by that point, and had forgotten about the insanity that comes with working with Puff.

I wrote a script in the weeks prior, and received approval from all relevant parties. But on the morning of the shoot, Puff’s manager arrived on set and told us they’d just watched the ending of Rocky 3, and wanted to pay homage to that scene. Sitting at the edge of the boxing ring, I frantically jumped into a rewrite.

Wahlberg soon arrived at the location — in his own car, alone. He walked in, quietly introduced himself, and told us he’d be ready when we were.

Minutes later, Puff arrived in a convoy of Sprinters. A group of thirty — friends, colleagues, videographers, photographers, publicists, his kids — entered into the gym with Puff, and they quickly ducked into a back room. When beckoned, I entered and walked them through the new script, and then we got to work.

After three takes, Puff’s manager clapped and said “That’s a wrap!” as everyone cheered. I ran to the ring and pleaded with Wahlberg that I needed one more take, for coverage. He corralled the entire crew back to work, and we got the shot. And then, just like that, Puff and his army were gone.

Every moment in Puff’s world was like this; a lucid dream in which you, a mere mortal, hung on for dear life.

And then there were the parties.

Puff’s White Parties of the ‘90s were the stuff of legend. I’d grown up on the photos, and imagined myself being there someday, flanked by my favorite artists, athletes, and filmmakers. But growing up in a Russian-Jewish immigrant family in suburban New Jersey, I felt as far away from Puff’s Hamptons house as humanly possible.

But twice during my time at REVOLT, I found myself entering the gates of his Miami mansion, by invitation from a friend who worked in his inner circle.

***

The first Puff party I went to was a choose-your-own-adventure swirl of 21st century celebrity.

On the way in, I saw Al Sharpton waiting in line for the bathroom. I passed by Macy Gray at the bar. And in between dance breaks — on a light-up floor, of course — my now-wife and I talked to The-Dream and told him his music was formative to our love story. “Oh, thanks! That’s so nice,” he said, standing beside his sister.

Elsewhere, Q-Tip and Drake went back-to-back on DJ duties. Machine Gun Kelly wandered around. Women in bikinis gyrated and danced in a pool that no one else entered. The Ciroc flowed at an ungodly pace.

And then, the seas parted for the arrival of the duo of the moment: Jay-Z and Beyonce. It was weeks after Beyonce’s self-titled album had come out and the pair took up position behind velvet ropes, ogled by their equally famous counterparts.

Around midnight, the DJ played “Drunk In Love,” and Jay and Bey came to the dance floor to celebrate among the commoners. My wife, eight Ciroc cocktails deep at that point, approached Beyonce to tell her she was an enormous fan. But she sobbed before any words actually came out, and Beyonce graciously thanked her.

Moments later, I approached Jay to tell him something similar, only to trip on someone’s foot on the way over and get clotheslined by his bouncer.

It was a big night. Then we got McDonald’s and went home. No freak-offs for us.

The main things I remember from my second time at Puff’s house are that I went with my brother, we drank a similar amount of Ciroc, and Puff never even showed up to his own party. At one point, we stood outside and watched his sons battle in a Step Up-style dance circle. It was decidedly less impressive than the first night, but still one of the better events I’ve attended.

Of course, we’d soon learn that there was a veiled darkness lurking in the shadows of every joyous night at Puff’s house.

***

“Did you see the Puff news???” dinged a text as I touched down in Miami. I was in town to visit my mom, and before the plane finished taxiing to the terminal, I zoomed through the New York Times report about his longtime girlfriend Cassie’s lawsuit.

In it, she alleged that Puff “controlled and abused her for years, beating her and forcing her to have sex with male prostitutes while he filmed the encounters.” She also accused Puff of raping her in 2018, and blowing up the car of one of her boyfriends. Details later emerged about enormous amounts of baby oil and dildos.

It was all, in a word, disgusting.

It was also oddly familiar, like a dispatch from a faraway place I immediately recognized. As I dug into the specifics, I believed every word and allegation, and could easily imagine every action as it unfolded. I suspect many people who were once in Puff’s orbit felt the same. This was not a good feeling.

When the Weinstein news came to light, I remember wondering what it would have been like to have worked at the Weinstein Company, in proximity to a monumentally problematic figure.

As it turns out, I know exactly what it would have been like.

The speed with which an entire industry turned on Weinstein showed me there was no doubt about his guilt; it must have been a widely-held secret. And while Puff’s sexual deviancy may not have been as known as Weinstein’s, his history of dubious behavior was. Still, we accepted it as the cost of doing business with a hip-hop giant.

***

“[Denial] isn’t even an option for you,” writer and filmmaker dream hampton told Puff, according to a recent interview with Rolling Stone. “Nobody is going to believe you. You’re already loathed. So you actually have an opportunity here to enter a different paradigm.”

Instead, in response to Cassie’s initial suit, Puff posted a video denying the allegations and revealing he had sought treatment for years of drug abuse.

The now-infamous hotel video — in which Puff beat and dragged Cassie down a hallway — released in the following months, stripped him of any remaining credibility, and again, remained largely unsurprising. The most surprising part was that he acted such a way in a public space.

But after having his actions quietly cosigned for so long, our society must have seemed like a playground where he could act as he wished. It was Puff’s world, we were just living in it.

To date, there have been dozens more lawsuits filed, in addition to a federal racketeering conspiracy and sex trafficking indictment. The latter led to his arrest in New York, where he is now being held without parole as he awaits trial. I continue to believe every word in every allegation, even if some of the suits are opportunistic.

In the meantime, we are left to tally the toll of Puff’s misconduct. How many lives did he ruin, directly or indirectly?

Aside from Cassie, who was signed to Puff for many years, many of Puff’s artists turned to religion and abandoned the music business entirely after working with him. Others accused him of brandishing wages earned from album sales and publishing. He was not a well-loved, artist-friendly executive.

Still, we amplified him at every level. He had a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. In 2020, he was awarded a career-spanning Industry Icon Honor at a Pre-Grammy Gala, and in 2023, he won the Global Icon Award at the MTV VMAs, just weeks before the Times report dropped.

But after his arrest, the culture — finally — took decisive action. Brands terminated their deals. REVOLT was wrested from his hands. Mayor Eric Adams revoked his Key to the City. Overnight, he was a pariah.

In the wake of his ostracization, I’ve been trying to figure out: when did we collectively agree that we could no longer stomach Puff?

We were all certainly onboard with his whole … thing … for as long as it served us, despite everything we knew. The reputation. The volatility. The whispers. The rumors. The power games. It was all toxic, but we could almost convince ourselves that it was all relatively victimless. Until it wasn’t.

***

Do you want to be great?

I hear this question differently, now.

What will you sacrifice of yourself in order to be great? What morals will you abandon? What will you allow, even if you never see it up close? And if you do see it, but avoid outing it for fear of putting your own position at risk, are you complicit?

I have a tendency toward evangelical optimism; I like to think that we are all ethical beings, willing to step up and stop evil things from happening. But in shadowy power structures like the ones Puff created at his companies, obedience to your leader and a dogged focus on success went hand-in-hand.

If you wanted to win, you had to be ruthless, and driven, and unforgiving in your pursuit. You had to demand what you wanted, and then you had to go get it. It was the only way. The Puff Way. (I do believe we all thought this only pertained to the work).

He made it easy to buy in, because success seemed to be on the other side. And despite my conflicted feelings about Puff before I ever worked for him, once I was at REVOLT, I leaned in, and was duly rewarded.

My time there led to incredible learnings, connections, and memories, and Puff literally paid my salary for several years, which happened to be double what I was earning at XXL. The boxing promo we made accelerated my career as a commercial director. I did all of this fully aware of the truths I had come to understand about Puff.

For as dark and depressing as his reign is in hindsight, it was fun and fruitful for those who benefited from it. We may have been party to an accused predator, making him wealthier through our efforts, but some of us did our best work in the process. Both things can be true.

And so, even as many of his former employees have moved onto new and exciting chapters, I have a hunch that in moments of self-reflection, we can’t help but wonder… If this person truly was a monster, were we not discerning enough to see it, or did we willfully ignore the signs?

The same thing happens when we learn of the impropriety of loved ones, doesn’t it? We first try to find ways to ignore, or deflect, or forgive, or wish away, until we have no choice to confront it. And now, after many years of feigned ignorance, we are forced, collectively, to confront the truth about Puff.

Lately, I’ve had a sneaking suspicion that we always knew who he was. He showed us. Maybe not everything, but enough. His brand was literally called “Bad Boy.”

We just didn’t want to see it, because he symbolized something so very American, something so appealing, we may have even wanted it for ourselves. That we could be great by being relentless; forcing people to bend to our will, all while curating a positive image on the world stage.

He may have represented the worst in us, but what does it say about us that we celebrated him — both privately and publicly — all along?